Histoire

Faits et divers

Description géographique et historique

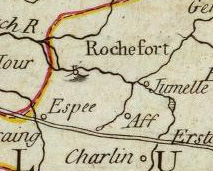

Thomas Kitchin,1788 |

|

|

vers 1650 Voyages dans les Pays-Bas espagnols, Duplessis l'Escuyer |

|

| septembre 1684 Il étoit neuf heures du matin , quand après un quart d'heure de pluïe, le vent tout à coup venant à écarter les nuages , les poufla dans une vallée, & nous préfenta à quelques cinq cens pas de Rochefort en Ardenne , un des plus beaux fpeftacles du monde. C'étoit un Iris tout nouveau. La matière qui le formoit n'étoit point courbée vers la terre pour eu faire un Arc-en-ciel , comme il arrive ordinairement, ni renverfée vers le Ciel, comme il arrive quelquefois. • C'étoient des nuages droits & perpendiculaires, à peu près comme de lougues colonnes, dont la première étoit verte , la féconde rouge, la troifiéme orangée, & la quatrième bleue, contre le mélange ordinaire des couleurs de ce météore. Ces colonnes étoient toutes claires & tranfparentes , & laiffoient voir diftinâement les objets qui étoient derrière, comme des bois , des collines, des châteaux &c. ; & quand elles vinrent à s'évanouïr , elles commencèrent par l'orangée & par la rouge. Lettre de Mr. Durondel à Mr. Bayle, 13 septembre 1684 |

|

| LA VILLE DE ROCHEFORT. C'Est la Capitale d'un Comté très ancien & considérable, nommé quelquefois le Comté des Ardennes. La Famille de Lœuwesteyn-Weirtheim l'a possédé en dernier lieu , & nommément le Comte Jean Ernest , Evêque de Tournai, qui mourut en 1741. Il avoit embelli considérablement le Château de Rochefort , où il faisoit fouvent sa demeure. Mais en l'an 1738, par sentence de la Chambre Impériale de Wetzelaer , après un procès qui a duré 200 ans, le Comte de Stolberg est devenu le propriétaire des Terres de ce Comté, qui dépendent de la Principauté de Liège; & pour celles qui font sous le Duché de Luxembourg , on poursuit actuellement le procès parde- vant le Confeil de la Province. JB Christyn ( mort en 1690) |

|

| 1768 ...Rochefort-belle & magnifique terre , vers les frontières de l'Evêché de Liège. A deux lieues de Rochefort eft le village d' Avein où les François gagnèrent une bataille fur les Efpagnols en 1635... (Les Pays-bas catholiques le Luxembourg Walon, Lenglet, 1768)

|

|

|

|

| 1816 Rochefort, a town of the Netherlands, in the territory of Luxemburg, with a castle, said to have been built by the Romans. It is situate on the Sommc, surrounded by rocks, 50 miles Nw of Luxemburg. Lon. 5 10 E, lat. 50 12 \ Brookes, A general gazetteer. |

|

|

10

et

11 Juin 1826

Te Rochefort gekomen, verzuimden wij

niet, om de grotte de Han te bezoeken, welke, zoo zij een

weinig racer bekend was, voorzeker de oplettendheid tot zich zoude

trekken van alle Natuuronderzoekers, die ZuidNederland doorreizen.

Rochefort ligt aan de

oevers van dc rivier P/Iomme, die in een zeer eng en bogtig

dal ftroomt. Zoodra men, van Dinant komende, de rivier is

overgegaan, vertoont de kalkgrond zich overal en wordt alleen

afgebroken door eene fchieferachtige Te St. Remi,

bij

Rochefort, was men bezig

aan het uitgraven van fraai rood marmer met witte aderen en gezwaveld

lood (Plomb fulfuré). Bij het dorp Hamer-enne,

tusfchen Rochefort en Han zagen

wij

opgegraven polypenhuizen, (Polypiers), behoorende tot het

gedacht der Tubiporae, (T. ftellata). Men vindt dezelve in

ronde tepelvormige (lukken van ondcrfcheidene grootte, aan hoopen langs

den weg liggen. Op de dwarfe breuk gelijken zij veel -naar de cellen

van een wespennest. Verslag van een

plant-landbouwkundig reisje...door Bronn en Courtois |

|

| 1835 De la grotte de Han , M. Nicolas et Gaspard se rendirent à Rochefort. Cette course leur plut beaucoup. Ils virent des ruines très pittoresques, les débris du château des anciens comtes de Rochefort, et, chemin fesant, un échantillon des Ardennes, des landes, des bruyères, de vastes plateaux tout couverts de genêts en fleurs , où quelques hameaux apparaissaient de loin en loin comme des îles de verdure au milieu d'une mer aux flots d'or. Nicolas au royaume de Belgique

|

|

| 1863 Rochefort, the ancient capital of the Earldom of Ardennes, is surrounded by sites of sylvan beauty and its position renders it worthy of fixing the tourist's or the botanist's attention. Coghland's Guide, 1863 |

|

| Un

repas

en Famenne en 1847 |

|

| The company consisted, besides

the host, of four trapping Ardennes farmers, in their blue blouses, and

four of the royal guard, in all the finery of spurs, tassels, and

worsted epaulettes. There was nothing very particular about them ; but

the dinner was a curiosity, and worth detailing, as a specimen of how

the substantial country-folks contrive to live in this part. After the

thin soup, and the meat from which the said trap had been

extracted, which are the first dishes presented an over the continent,

there was placed on the table by a heavy-built damsel, with naming red

petticoat and massive gold ear-rings, a huge dish of smoking mutton

cutlets, with apple-sauce, flanked by dishes of carrots and potatoes ;

then came a platter of shelled beans stewed, a common dish here ; then

an immense bowl of apples, cut into halves, and stewed, followed by

roast fowls, with excellent mushrooms -, and then some preparation of

meat, which I could not identify by taste or sight, and exceedingly

tough. By this time our appetites were pretty well blunted ; but the

carver, appeased, began whetting his blade, and all was expectation,

till a noble Ardennes ham made its appearance, forest-fed, and with a

strong smack of what we may fancy to be the wild-boar flavour,

supported by craw-fish, smoking hot, and no less than four immense

fruit-pies, served up in wicker platters, and a foot at least in

diameter. For the whole repast, the sum asked was one franc (nincpence

three-farthings), and for which we might have had fruit and coffee in

addition if we had pleased. The raw materials at home could hardly have

been given for three times the sum.

|

|

| |

|

|

1869: IN THE HEART OF THE ARDENNES BY FLORENCE MARBYAT (MRS. ROSS CHURCH) Fever

is raging in Brussels, and we are advised to quit the town

as soon as possible. The question is, where to go. I suggest Rochefort in the Ardennes, having

ascertained previously that the place is healthy; but my friends laugh

at me. " Rochefort in February! We

shall all be frozen to death." "At least," I argue, " there is pure air

to breathe." " But you can have no idea of the dulness," is all the

reply I receive; " Rochefort, with its

one street and its one resident, is bad enough in the summer, but at

this season it will be unendurable." Tet I am not to be turned from my

purpose. I consider it is better to be frozen outwardly than burned

inwardly; and that when one is flying from a pestilence there is no

time to regret the numerous pleasures left behind, or the few that loom

in the future. And so we settle finally that, notwithstanding its

promised disadvantages, we will thankfully accept the refuge Rochefort can afford us; and having made up

our minds to go, we start twenty-four hou:rs afterwards. Being pent-up in a railway-carriage with half-a-dozen manikins and womanikins, who suck oranges half the time, and obtrude their little persons between your view and the window the other half, is not perhaps the most favourable situation from which to contemplate the beauties of nature; for which reason, perhaps, it is as well that for the first part of our journey nature presents no beauties for our contemplation, and thereby our naturally mild tempers are prevented from boiling over. But when we have accomplished about fifty miles (Rochefort being distant from Brussels seventy miles), the country begins to assume a different and far more engaging aspect. The flat table-land, much of it marshy and undrained, which has scarcely been varied hitherto, gives place to swelling hills, half rock, half heather; and charming copses of fir, some of which are very extensive. The scenery becomes altogether more wooded and naturally fertile-looking; and houses and farmsteads lose all trace of British contiguity, and become proportionately interesting to curious English eyes. The train is an express; and as it dashes past the fragile, roughly-built little stations with which the road is bordered, it is amusing, or rather I should say it would be amusing, did it not suggest the idea of accidents, to see the signal-flags displayed by peasant-women in every variety of attitude and costume. Here stands a stolid, solid Belgian girl, of eighteen years of age probably, and stout enough for forty, with a waist like a tar-barrel, and legs to match, who nurses her flag as if it were a baby, and gazes at the flying train with a countenance which could not be more impassive were it carved in wood. "We have hardly finished laughing at her, when the train rushes past another station, at which appears a withered old crone, her head tied up in a coloured handkerchief, and her petticoats, cut up to her knees, looking cruelly short for such a wintry day, and displaying a pair of attenuated legs and feet for which the huge wooden sabots look miles too large. She waves about the signal-flag in a nervous, agitated manner, which suggests the idea that she is not quite sure whether she hns caught up the right one or not; but before we have time to be made uncomfortable by the fact, we are passing another of these Belgic " shanties," at the door of which appears for a moment a middle-aged woman, who waves the signal at us in a menacing manner, and rushes back immediately to her children or her cooking. Remembering our own signalmen, and the importance attached to their capabilities and education for the important office assigned them, it ceases to be a matter of amusement to see the lives of hundreds daily intrusted to the direction of such ignorant creatures as these. I suppose that "Monsieur," smoking at his ease by the fireside in the little wooden station-house, directs the actions of his mother, wife, or daughter; but what are the authorities about not to insist on his performing his duty himself?

Here we all unpack ourselves; and a buxom German landlady, with a kind motherly face, comes down the steps to greet us. She-has received my letter; the beds are all ready for us; the dinner will be on the table in half an hour; we are to be pleased to enter, and make ourselves at home. We are very pleased; for we are dreadfully tired (not cold, for the weather is unnaturally mild), and have not had anything substantial to eat all the day. We climb up the steps of the hotel, which looks just like a farmhouse abutting on the main street, and find ourselves in a sanded room, containing a long wooden table, with benches either side of it, and bearing evident reminiscences of smoking and drinking—in fact, " not to put too fine a point on it," the public taproom—but where we are met by the landlady's two eldest daughters, Ther^se and Josephine, who are beaming in their welcome. They usher us into a second room, where the children scream at the sight of a table laid for dinner, and the four corners of which bear bowls of whipped cream and custard, and rosy Ardennes apples, and biscuits just out of the oven. The little people want to begin at once, and cannot be brought to see the necessity of washing their faces and hands first, or waiting till the meat and potatoes shall be placed upon the table. Would Madame like to see the chambres-a-coucher at once ? Madame saying yes, Therese catches up the youngest child but one, and, preceded by Josephine, we enter first a scullery, next a bricked passage, thence mount a most perilous set of dark narrow stairs, and stumble into a long whitewashed corridor, which terminates in a glass-door opening on to a garden. Here three doors successively thrown open introduce us to our bedrooms; and the trunks having been brought up the breakneck stairs, we take possession at once. The little whitecurtained beds are small, but beautifully clean, and each one is surmounted by its eider-down quilt in a coloured-cotton case. Two little islands of carpet in a sea of painted boards represent the coverings of the floors; and the washing-stands are only deal-tables, and there are no chests of drawers; but we inhale the fresh vigorous breeze which is pouring through the windows (open even at that season), and think of fever-infected Brussels, and are content. But though it is all very nice and clean, we cannot possibly wash without water, nor dry our hands without towels. An imbecile shout from the door for anybody or anything brings a broad-featured, rosy, grinning German girl to our aid, who, when she is asked her name, says it is Katrine, but we can call her by any name we please. The pronunciation of " Katrine" not presenting those difficulties to our foreign tongues which the owner of it seems to anticipate, we prefer to adhere to her baptismal cognomen, instead of naming her afresh, and desire Katrine to bring us some hot water and towels; on which she disappears, still on the broad grin, and returns with a pail of warm water, which she sets down in the middle of the room. We manage well enough with that, however, but are at our wits' end when, on being asked for more of the same fluid with which to mix the baby's bottle, she presents it to ns in a washing-basin. But as, a few minutes after, I encounter her in the corridor carrying a coffee-pot full to E 'sroom, I conclude that in Rochefort it is the fashion to use vessels indiscriminately, and resolve thenceforth to take the goods the gods provide without questioning. On descending to the dining-room, we find that the gods have been very munificent in their gifts. After the soup appears roast beef; and as we are very hungry, we cause it to look foolish, and are just congratulating each other on having made an excellent dinner, when in trots Therese, pops our dirty knives and forks upon the table-cloth, whips away our plates, with that which contains the remainder of the beef, and puts down a dish of mutton-chops in its stead. We look at one another in despair; we feel it to be perfectly impossible to begin again upon mutton-chops, and I am obliged to hint the same to Therese in the most delicate manner in the world. She expostulates; but to no purpose, and leaves the room, mutton-chops in hand. But only to give place to her mother, who enters with a countenance of dismay to inquire what is wrong with the cooking that we cannot eat. Nothing is wrong ; we have eaten remarkably well. It is our capabilities of stowage which are at fault. Will we not have the hare, which is just ready to be served up ? Sorry as we are to do it, we must decline the hare; and as we affirm that we are ready for the pudding and nothing else, we feel we have sunk in Madame's estimation. The pudding, a compote of apples and preserves, with the whipped cream and custard, is delicious; and as soon as we have discussed it, we are very thankful to stretch ourselves under the eider-down quilts, and know the day to be over. We have done work enough that day to entitle us to twelve hours' repose; yet we are all wide-awake with the first beams of the morning sun. We dress ourselves with the pleasurable anticipation of seeing new things, however simple, and come down-stairs to a breakfast-table in its way as plentifully spread as the dinner-table of the night before. We have an abundance of milk,—so fresh from the cow that it is covered with froth, and the jug which contains it is quite warm,—eggs, cold meat, home-made bread in huge round loaves, good butter, and strong clear coffee. In fact, we come to the conclusion that our landlady knows how to live, and we no longer marvel at the rosy cheeks and full forms of Therese and Josephine, nor that Madame herself fills out her dresses in such a magnificent manner. E has been for a stroll before breakfast, and brings back a report of ruins on the high ground; he has already unpacked his sketchbooks and sharpened his pencils. We, not being walking encyclopaedias, Beize our Continental Bradsliaw, and find that the ruins are those of a castle in which Lafayette was made prisoner by the Austrians in 1792. As soon as breakfast is concluded, we rush off to see the mined castle, which stands on an eminence just above the hotel, and which our landlady (who walks into our sitting-room and takes a chair in the most confiding manner possible whenever she feels so inclined) informs us, although not open to the public, belongs to a lady whose house is built on the same ground, and who will doubtless allow ns to look over it. We can see the remains of the castle before we reach them, and decide that it must]] have been uglier and less interesting when whole than now, having been evidently designed with a view to strength rather than beauty. The little winding acclivitous path which leads to it, bounded by a low wall fringed with ferns and mosses, is perhaps the prettiest part of the whole concern; but just as we have scaled it, and come upon the private [dwelling-house, our poetic meditations are interrupted by the onslaught of half-a-dozen dogs (one of which is loose, and makes fierce snaps at our unprotected legs), which rush out of their kennels at chains' length, and bark so vociferously, that we feel we have no need to make our presence known by knocking at the door. A child appears at it; and we inquire politely if we may see the ruins, at which she shakes her head, and we imagine she doesn't understand our Parisian French. But in another moment we are undeceived, for the shrill, vixenish voice of a woman (may dogs dance upon her grave!) exclaims sharply from the open door, " Fermez, fermez; on ne pent pas entrer." The child obediently claps it to in our faces, and we retrace our steps, with a conviction that the lady is like her castle—more strong than beautiful. E is so disgusted that he will not even sketch the ruins from the opposite side of the road, up which another precipitous path leads ns to a long walk, which in summer] must be a perfect bower, from the interlacing of the branches of the trees with which it is bordered; and from which we have a far better view of the ruins than the utmost politeness of their owner could have afforded us. But no; judgment has gone out against them; we decide they are heavy and unpicturesqne, and not worth the trouble; and we walk on in hopes of finding something better : and are rewarded. At the close of the long overshadowed walk, a quaint little chapel, beside which stands a painted wooden crucifix nearly the size of life, excites our curiosity, and, walking round it, we come upon one of the loveliest scenes, even in the month of February, that Nature ever produced. A green valley, creeping^in sinuous folds between two ranges of high hills; one rocky and coated with heather, the other clothed with wood. Beneath the rocky range there winds a road bordered by trees> —along which we can see the red diligence which brought us from the ... taking its jangling way,—and beside it runs a stream, terminaling in a cascade and a bridge, and the commencement of the lower part of Rochefort. All the fields are cut upon the sides of hills, and are diversified by clumps of rock covered with ferns, and usually the groundwork of a well, protected by a few rough planks, or the fountainhead of a mountain-stream which trickles down until it joins the river. This is the valley of Jemelle, to see which in the proper season would alone be worth a journey to Rochefort. We look and admire, and lament the impossibility of ever transferring such a scene to canvas as it should be done; and then we turn back whence we came, and find we are standing at the entrance of an artificial cave, situated at the back of the crucifix before alluded to, and which forms perhaps as great a contrast to the natural loveliness we have just looked upon, as could well be. Apparently it is the tomb of some woman, by the framed requests which hang on either side that prayers may be offered for the repose of her soul; but had her friends turned out upon her grave all the maimed and motley rubbish to be found in a nursery playbox of some years' standing, they could scarcely have decorated it in, a less seemly manner. At the end of the cave is a wooden grating, behind which is exhibited one of those tawdry assemblages of horrors which tend more perhaps than all else to bring dishonour on the Roman-Catholic religion, so utterly opposed are they to our conceived ideas of what is sacred. Two or three rudely-carved and coarselypainted, almost grotesque, wooden groups of the dead Christ, the Holy Family, and the Crucifixion, form the groundwork of this exhibition ; the interstices being filled up with gold-and-white jars of dirty artificial flowers; framed prints of saints with lace borders, reminding one of the worst description of valentines ; and composite figures, supposed to represent the same individuals, and which may have cost fifty centimes apiece. The collection is such as to make the spectator shudder to see holy things so unholily treated; and it is difficult to conceive how, in this century, when art has been carried to such a pitch that even our commonest jugs and basins have assumed forms consistent with it, anyone, even the lowest, can be satisfied with such designs and colouring as these things display. Returning homeward

by the lower part of the town, we pass a maiton retigieuse dedicated

to

St. Joseph, and in the garden see the good little sisters joining

their pupils, to the number of forty or fifty, in a merry game of "

Here we go round the mulberry-bush," and apparently taking as much

pleasure in the exercise as the youngest there. The church and

churchyard stand at this end of Rochefort. There

is

nothing in the building to attract one's notice, except that we

agree that it is the ugliest we have ever seen; but we walk round the

little churchyard, the paucity of graves in which speaks well for the

climate of the place. The crosses and railings, made of the commonest

wood and in the most fragile manner, are all rotting as they stand or

lie (several having assumed the recumbent position); and we are leaving

the spot with the conviction that we have wasted five minutes, when we come against a crucifix fastened by heavy iron clamps against the wall of the church. A common iron cross, rusty and red from damp and age, with a figure nailed on it of the most perfect bronze, old and hard, and dark and bright, and as unchanged by weather and exposure as on the day (perhaps hundreds of years ago) it was first placed there. Toiling up the

street again, and examining the shops as we go, I say that, much as I

like Rochefort, I do not advise anyone

to come here in order to purchase their wedding trousseau, or

lay-in a stock of winter clothing. We look in vain for something to buy

in remembrance of the place; but can see nothing out of the way, except

it is a yellow teapot, holding at the least four quarts, and with a

cnrled spout to prevent the tea coming out too fast, which must be

almost necessary with such a load of liquid. The teapot is delicious,

and quite unique; but scarcely worth, we think, the trouble of

transportation. "We have but just decided this matter to our

satisfaction when we come upon a " miscellaneous warehouse," upon whose

front is painted " Carles pour les grotles de Rochefort" and remember that we must

see the famous grotto, and turn in to ask the price of admission. Five

francs a-head; children half-price. We think the charge is high; but Monsieur C

(to whom the grotto belongs) takes us into his house stops to consider his commas) that it is " tresbeautresbeautresbeau.'" However, we agree to return the next day at eleven o'clock, when he promises the guides shall be in readiness for us; and we go home to another excellent dinner, the pleasure of which is only marred by the fact that Thernse tcill make us use the same knives and forks for every course; and we haven't the strength of mind to resist. Yesterday I spoke to Madame on the necessity of engaging someone during the mornings to read French and German with the girls, as we shall most likely be here for a month; and it is too long a time for them to be idle. Madame did not think I should find a demoiseille in Rocheforfc who could instruct them; but there is aprofesseur here who has passed all his college examinations, and who, if he has the time, will doubtless be very glad of the employment. I asked her to send for the professeur that I might speak to him on the subject; and here, just as we have done dinner, he arrives; for Madame throws open the door, and with a certain pride in her voice (pride that Rochefort should possess such an article) announces "Monsieur k Professeur." I glance up, thinking of Charlotte Bronte and her professor, and hoping this one may not prove as dirty and seedy and snuffy, and, to my amazement, see standing on the threshold a lad of about seventeen or eighteen, dressed in green trousers and a blue blouse, and holding his cap in his hand. The two girls immediately choke, and bury their faces in their books, which renders my task of catechising rather a difficult one; and I glance at E for aid, but his countenance is almost level with the table as he pretends to draw. So I fiud there is nothing to be done but to beg the professeur to be seated,—a request which he steadily refuses to comply with; and as he stands there, twisting his cap in his hands, he looks so like a butcher-boy, that it is a mercy I do not ask him what meat he has to-day. But the poor young man is so horribly nervous, as he tells me that, though qualified for a tutor, he has never taught before, that I have not the heart to refuse him on account of his youth: besides, is he not the sole professeur in Rochefort ? So I give him leave to come the neit morning, and try, at all events, what he can do with the girls; and he looks very happy for the permission; and we see him, a minute afterwards, striding proudly down the street, whistling as he goes, and holding his head half an inch higher for having " got a situation." Of course the children make merry over him for the rest of the evening, and cannot recall the appearance of their professeur without shrieks of laughter; but he comes the next morning, nevertheless, to commence his duties, and proves to be quite as particular as older teachers', and much more competent than some, and takes the youngest girl completely aback by telling her she shall be punished if she is not steady. At eleven o'clock the next morning we are all ready to view the grottoes, and E and I, with the two eldest children, start off on oar expedition. The way to their entrance lies through Monsieur C ***'s park, which in summer must be a very charming resort. He has collected here all the wild animals indigenous to the Ardennes, and shows them to us as we walk to the mouth of the grottoes. Close to his house he has a splendid wolf and three foxes—the golden, silver, and common fox. I should have preferred to keep these interesting fpecimens a little farther off from my own nose; but there is no accounting for tastes. In the aviary he has squirrels, guinea-pigs, doves, 1'igeons, and the most magnificent pair of horned owls I have ever seen. These birds, which are as fierce as possible, have eyes of jet and amber, as big as half-crowns; and when in their rage they spring at passers-by, they make a noise with their beaks just like castanets. A little farther up the park, we come upon

the Ardennes deer, which are thicker built and less graceful than the

English fallow-deer, with which they are consorting; nnd a wild-boar,

with fierce tusks and a savage grunt, wallowing in & parterre of

clay,

which nevertheless knows his master, and puts his ugly snout out

to be scratched between the I confess that as I go down the second time I feel a little nervous, and my limbs shake. I don't like this going down, down, down into the shades of eternal night, with no companions but two littfe children. But at last we stand on level ground again; there is no light anywhere except from the guides' lamps; the foremost one (who is always spokesman) waves his above his head, and introduces la grande sA I look up and around me, but all is black as pitch. I feel that I am standing on broken flints and a great deal of mud; and as the guide's lamp throws its faint gleam here and there, I see that the cavern « stand in is very vast and damp, and uncommonly like a huge cellar; W I can't say I see anything more. In another minute the guide has turned, and leads us through a passage cut in the rock. We are not going up- or down-stairs now, but picking our way over slippery stones ambetween places sometimes so narrow and sometimes so low, thatoBr ; ihenldere get various bumps and bruises, and the guide's warning of "Garde tete!" sounds continuously. Every now and then we come upon a larger excavation, which is called a sails, and given some name consequent on the likeness assumed by the stalactites contained in it. Thus one is called salle de Brahma, because it contains a large italactite, somewhat resembling the idol of that name. Another, talk du sacrifice, because its

principal attraction is a large flat stone, at the foot of which is

another, shaped sausage-wise, and entitled tombeau de la victime. We

pace

after the guides through these The " glittering" stalactites are nowhere. The cave is lined with stalactites, but (with the exception of a few white ones) they are all of a uniform pale-brown colour, and have no idea of glittering or being prismatic. The greatest wonder of the grotto is its vastness, which may be estimated from the fact that we are two hours going over it, and then have not traversed the whole on account of fresh works being carried on in parts. We penetrate to its very depths to see the river md the waterfall, but the mud is so excessive that we are compelled 'fi stop, and let the guide descend with his lamp and flash it over the ifater, which is really very pretty, and, strange to relate, contains good rout. Then we plough our way upwards again; up fungus - covered adders, and wet slippery stairs, upon which it is most difficult to :eep a footing, until we arrive at decidedly the finest sight there—the '.die du salbat. Here the guides send up a spirit-balloon, to show is the height and extent of the vast cavern, and we are rather awetruck, particularly as, in order that we may see the full effect, the ither guide plants us on three chairs and takes away both the lamps, saving us seated in the darkness, on the edge of a precipice. The lackness is so thick about us that we can almost feel it; and the ilence is that of death. My youngest girl slips her little hand in mine, and whispers," Mamma, supposing he weren't to come back again!: and I can't say the prospect pleases. However, the balloon reaches the top of the cavern, and is hauled back again; and the guide dots come back; and, whilst he is assisting his fellow to pack it away, I sing a verse of " God save the Queen," for the children to hear the echo, which is stupendous. Then we see the prettiest thing, perhaps, we have seen yet. At the top of the salle du sabbal there is a kind of breakage in the side, ; a large cluster of stalactites. One guide climbs up to this place anc holds his lamp behind the group, whilst the other calls out " k femmt qui repose;" when lo! before us there appears almost an exact representation of a woman, reclining with crossed legs, and a child on her bosom. It is so good an imitation, that it might be a figure carved in stone and placed there, and I think the sight gave us more pleasnre than anything in the grotto. We have come upon several groups o! stalactites already, to which the guides have given names, such as range de la resurrection, foreillc de Tttephant, and le lion Belye; but though they have, of course, borne some resemblance to the figures mentioned, the likeness is only admitted for want of a better. This likeness, however, is excellent, could hardly be more like; and we are proportionately pleased. With the salle du sabbat and the balloon the exhibition is ended; and we are thankful to emerge into the fresh air again, and to leave slippery staircases and the smell of fungi behind us. We feel very heated when we stand on the breezy hill again, for the grotto, contrary to our expectation, hns proved exceedingly warm, the exercise has made us feel more so; and daylight looks so strange that we can scarcely persuade ourselves we have not been passing the night down below. We have picked up several little loose bits of stone and stalactite during our progress, and when we reach home, we spi them out before us on the table, and try to remember where they came from. Here is a bit of marble, veined black-and-white; and here is white stone, glistening and silvery. Here is the stalactite, a veritable piece of " frozen tears" and couchant hmtris. Well, we have been a little disappointed with the grottoes of Rochefort, perhaps; we have not found the crystallisations quite so purple-and-amber as we anticipated, or the foundations quite so clean but, after all, it is what we must expect in this life. If the grotto not so brilliant as we expected, it is at least a very wonderful and uncommon sight; and so in this life, if we can but forget the pnrpl and gold, we may extract a great deal of amusement from very smal things, if we choose to try. With which bit of philosophy I conclnde. |

suite